Is your company thinking about implementing new ideas in the form of a service or product?

In order to learn if an idea has a chance to succeed, it needs to be validated first. We often hear about how a lack of budget and the inability to execute lead to an idea failing, but the lack of proper idea validation is usually the root cause. Simply put: bypassing this vital process can be catastrophic.

On the surface, idea validation (also known as concept testing) sounds like an expensive, complex and time-consuming affair but the truth is, this heart-beating process simply helps you to break down an idea into a viable business concept before you spend time and money on the idea. The end goal is to figure out if an idea is something that consumers want or help solve the problem and ensure that it is something people would pay for. This can save a company from investing hugely on process changes or a new full on production line or the basis of a new startup, but only to find out that the product is a dud.

Whether you are a large corporation or an early stage start-up, getting an idea validated properly is crucial. Throughout history there have been many instances of organisations that invested a great deal of resources into a certain product to bring it to market, only for that investment to turn out to be an extremely costly disaster. Some famous examples include the Amazon Fire smartphone, Crystal Pepsi, The New Coke, Google Glass and many more. As you can see, even well-known multinational corporations are prone to such failures, and the need for idea validation extends to everyone including the companies on both ends of the organisational spectrum.

There is a comprehensive process that an idea must undergo in order for it to be validated, and this goes beyond just talking to a couple of people on the street who are assumed to be your target consumers! Doing research on Google keyword planner for your idea does not serve the full purpose of idea validation either.

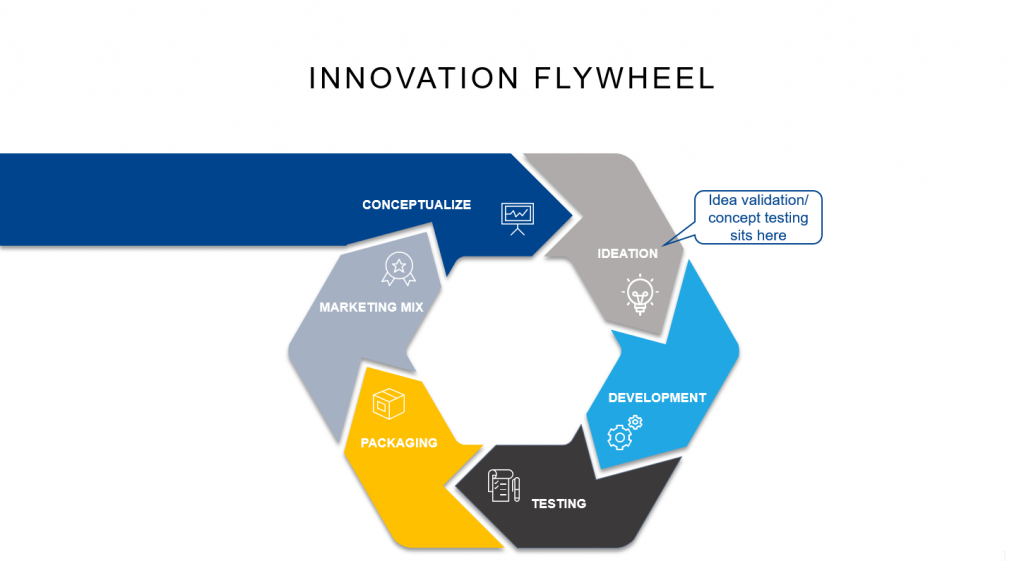

Before going into the steps of idea validation, here’s a visual overview of a our Innovation Flywheel, outlining the different crucial stages of the innovation process:

For every new idea created, developed and brought to the market, ideation serves as a crucial step that must occur before the idea is put into practical development. This part of the innovation flywheel is where ideas are expanded on, tested, and validated before proceeding to a stage where a larger amount of resources is invested into the product.

So how is idea validation carried out?

One of the first steps of idea validation is to gather feedback on the idea/product. This is done by creating a representation of the idea/product that can be shown to the target consumer for them to provide feedback. In order to do this, we would need to decide what format should be used to create that representation.

The following is a list of formats that could be used, and each successive format brings an increasing level of depth and accuracy in the expression of the idea/product, which potentially yields more accurate feedback for the idea validation:

Idea formats to carry out idea validation

- Text – A textual explanation of the idea/product in question.

- Images – Photos or graphics that provide a visual representation of the idea/product.

- Video – A video that allows the involved parties to see how the idea/product could theoretically work in motion.

- Product Mock Up – A physical but non-functional representation of the idea/product that provides an idea of how the product would look/feel and be experienced once created. Also called a Proof-of-Concept (PoC).

- Working Prototype – A fully functional iteration of the idea/product.

When picking a format, it’s important to keep in mind the costs of each format and whether it is suited for the idea/product that needs to be tested. Each successive level is more costly than the last, and going as far as creating a working prototype may not always be necessary in order to collect adequate feedback.

For example, if the product being created is a car, then it is best to use a working prototype as building a specific production line for a car model is extremely expensive, and creating a single working prototype would only be a small cost relative to the potential cost of the production line in its entirety. Furthermore, a car is also a product that needs to be experienced directly in order to gain accurate feedback that would reflect how consumers would actually react to the final product.

However, for more malleable ideas/product such as information or educational courses, there is no heavy upfront investment into production lines and the product itself doesn’t need to be experienced physically. In these cases, using one of the cheaper formats such as text-based would be more appropriate.

After choosing a format, the idea testing phase can proceed, where the ideas/prototypes are presented to the test audiences to figure out the potential success of the idea/product based on what we deem as the 2 key metrics:

1.) Whether consumers like the idea.

2.) Whether the consumers think the idea is unique or not.

The success of the test on these two metrics will yield a value on a matrix as seen below.

An optimum result here would be if the idea is BOTH liked and unique.

An optimum result here would be if the idea is BOTH liked and unique.

A decent result would be if the idea/product is deemed unique even if it is not well liked. This is not necessarily bad as it means that the idea has interesting potential. Audiences don’t fully appreciate the idea yet and it might be successful with some fine tuning, so the idea could become more well-liked by potential consumers in the future, or consumers can be ‘educated’ to like it – something great marketers can potentially do.

This could actually be seen as more desirable than the reverse scenario where the product is liked but not unique. This is known as a ‘me-too’ product – a product that is already very similar to existing products in the market. In this case, the success of the product would rely on finding your niche or unique value proposition to appeal to consumers.

In a worst case scenario, the product is not liked and not unique. Therefore, this process will at least have saved the company from investing any further on a hopeless product – back to the drawing board!

Getting the Total Addressable Market

If the database used for research in the idea validation process is truly representative of the population of an AREA or COUNTRY. Then, we would be able to project a Total Addressable Market for the product.

A representative database represents a proper population breakdown which specialised market research firms such as Oppotus can provide.

By having a representative database, you are able to:

- Project the total addressable market (TAM) for the product (that liked your idea), and;

- Profile this market group for characteristics such as age, gender, income groups and so on. This will prove extremely useful down the line when the organisation wants to carry out marketing/promotions for the new product and need to target better.

By knowing the exact profile of the target consumer base, your organisation would have all the data needed to carry out targeted ads or even micro-targeting. You would be able to buy Facebook ads at the most efficient rate possible thanks to the data on hand that will accurately guide any marketing campaigns, rather than just basing your marketing on assumptions or broader demographic knowledge that isn’t as deep as a well profiled TAM.

Ensuring Result Accuracy

Another crucial factor when carrying the ideal validation process is to ensure that mental biases do not affect the result of your validation.

Humans are very susceptible to mental biases when they are asked to answer questions before giving feedback and making decisions. These mental biases can cause people to give different feedback depending on something as minute as the order in which certain questions are asked.

One example of a possible mental bias is anchoring. This is when the consumer’s opinion relies very heavily on the first piece of information offered to them, causing them to give inaccurate information for your idea validation process because their thought process has already been affected by the information given to them. For example, if a consumer is shown a version of a product that costs $200, another version of the product that costs $100 will be seen as very cheap, which might cause an overwhelming 80% of consumers to claim they would buy it, even if $100 is actually the standard price of the product. On the other hand, if the $100 price-point was shown to consumers first, then the conversion rate to sales may not turn out to be as positive in reality.

There isn’t enough time to go through every single one of the possible biases and how they can affect the results of a study, but any study you carry out must be carefully designed to negate these biases as much as possible if your organisation wants to have any hope of gathering accurate information in your idea validation process.

One way to do this is to craft the questions in your test in a certain way. It’s vital that your questions are ordered so that high level questions are asked first before moving on to more specific questions, as starting with specific questions has the tendency to cause subjects to anchor expectations.

For example, if we wanted to ask users to give feedback on a certain bank called Bank A, it would not be advisable to start off by asking a series of micro questions along the lines of “did you like the attitude of the staff?”, “did you like the layout of the ATM lobby?” and “how did you find the usefulness of the financial advisor?” before finally asking the user: “Are you happy with Bank A?”

In the case that the user responds positively to the initial questions, they will be much more likely to say “Yes, I am happy with Bank A” as their overall opinion has been anchored to give positive feedback, hence creating a biased result.

However if we started with a more general questions like “how do you like Bank A?”, then the user is more likely to provide a holistic picture. From there we can follow-up with more questions that gradually become increasingly detailed. This leads to a purer results that more accurately reflects how the consumer processes information and arrives at their perceptions by going from macro to micro, and not the other way around.

Another way to get more accurate feedback during the idea validation process is to ask consumers to rate the idea on a scale rather than asking basic yes or no questions about how they feel regarding the idea.

For example, we would first ask the consumer to rate their “overall liking” of the idea on a scale of 1-5, with 1 meaning that they “do not like it at all” and 5 meaning that they “like it a lot”.

After that, we would then ask someone to rate their intention to purchase the product without considering price. People who aren’t well-versed in market research may not bother to ask such a question, but the fact of the matter is that just because someone likes an idea doesn’t necessarily mean that they intend to buy it. This would also be graded on a scale of 1-5, where 1 means that they definitely would not buy it, and 5 means that they would definitely buy it. The reason we make it clear to take away the pricing element here is because we don’t want consumers to consciously or unconsciously consider the price factor. This would add another layer of variability which would reduce the accuracy of the feedback.

Then, to get an even more accurate representation of how consumers would react to an idea when it is actually on the market, we would ask them to rate their purchase intention at a particular price on a scale of 1-5. This would give us a much better idea of how willing consumers would be to make the purchase at market price, compared to a survey where consumers are only asked whether or not they like something.

To evaluate pricing more thoroughly, we could even ask a further series of questions about the pricing of a product using what is known as the price sensitivity measure (PSM). The PSM is a very useful measurement tool because it allows us to figure out the realistic optimal price for the product, allowing us to figure out how to price the product attractively for consumers while still being able to turn a profit, before the item is even placed on the market. Since it is such a useful tool, we will take a more in-depth look at PSM in a future article.

Conclusion:

Spending on market research can be seen as a waste of money for some. However, as you can see in this article, making the investment to hire a skilled researcher like Oppotus can save you MILLIONS or HUNDREDS OF MILLIONS before investing in that expensive factory production line, as we will be able to conduct accurate and nuanced studies that have been carefully designed to eliminate biases and deliver the truth to your organisation.

We provide accurately calibrated results through tried and true proprietary research processes which ensure that your organisation will receive the correct information that it needs to make well informed business decisions.

Our studies can also help with product iteration, and carve a path forward for product development.

So if you have an idea in the pipeline that you would like to test and validate, feel free to contact us.